When Training an LLM is Transformative

In my last post, I commented on the two recent court victories for Meta and Anthropic and summarized the judgements that were made in favor of fair use for the training of LLMs. In these two specific cases, the training of LLMs has been deemed transformative. However, the two judges disagreed whether or not LLMs are harming the market of the material they're being trained on, which is a critical point for fair use consideration. Ultimately, both judges ruled in favor of fair use, but for the case against Meta, I think that was only because the author's suing them (or at least... the lawyers they hired) did not argue that Meta was harming the market for their books. Judge Chhabria said,

[This] ruling does not stand for the proposition that Meta’s use of copyrighted materials to train its language models is lawful. It stands only for the proposition that these plaintiffs made the wrong arguments and failed to develop a record in support of the right one.

The Importance of Filters

But the question of market harm and/or replacement was the focus of the other post. In this one, I want to discuss the notion that training LLMs is transformative. US District Judge William Alsup aptly described the LLM training process,

Anthropic used copies of Authors’ copyrighted works to iteratively map statistical relationships between every text-fragment and every sequence of text-fragments so that a completed LLM could receive new text inputs and return new text outputs as if it were a human reading prompts and writing responses.

For the case involving Anthropic, distinctions were made between four types of copying of copyrighted materials to determine if the use of those materials to train the LLM that powers Claude was transformative. The first three were somewhat trivial[1], but the fourth requires nuance. Judge Alsup states,

[Each] fully trained LLM itself retained “compressed” copies of the works it had trained upon [...]. In essence, each LLM’s mapping of contingent relationships was so complete it mapped or indeed simply “memorized” the works it trained upon almost verbatim. So, if each completed LLM had been asked to recite works it had trained upon, it could have done so.

However, the authors did not allege copyright infringement for anything that Claude produced. This was was because of the filters for the inputs and outputs of Claude that Anthropic has implemented. This critical detail was also central to Meta's defense, where Judge Chhabria ruled that Meta's copying of copyrighted materials was transformative, because Meta's post-training made it such that "even using “adversarial” prompts designed to get Llama to regurgitate its training data, Llama will not produce more than 50 words of any of the plaintiffs’ books."

When Training an LLM is Definitely Not Transformative

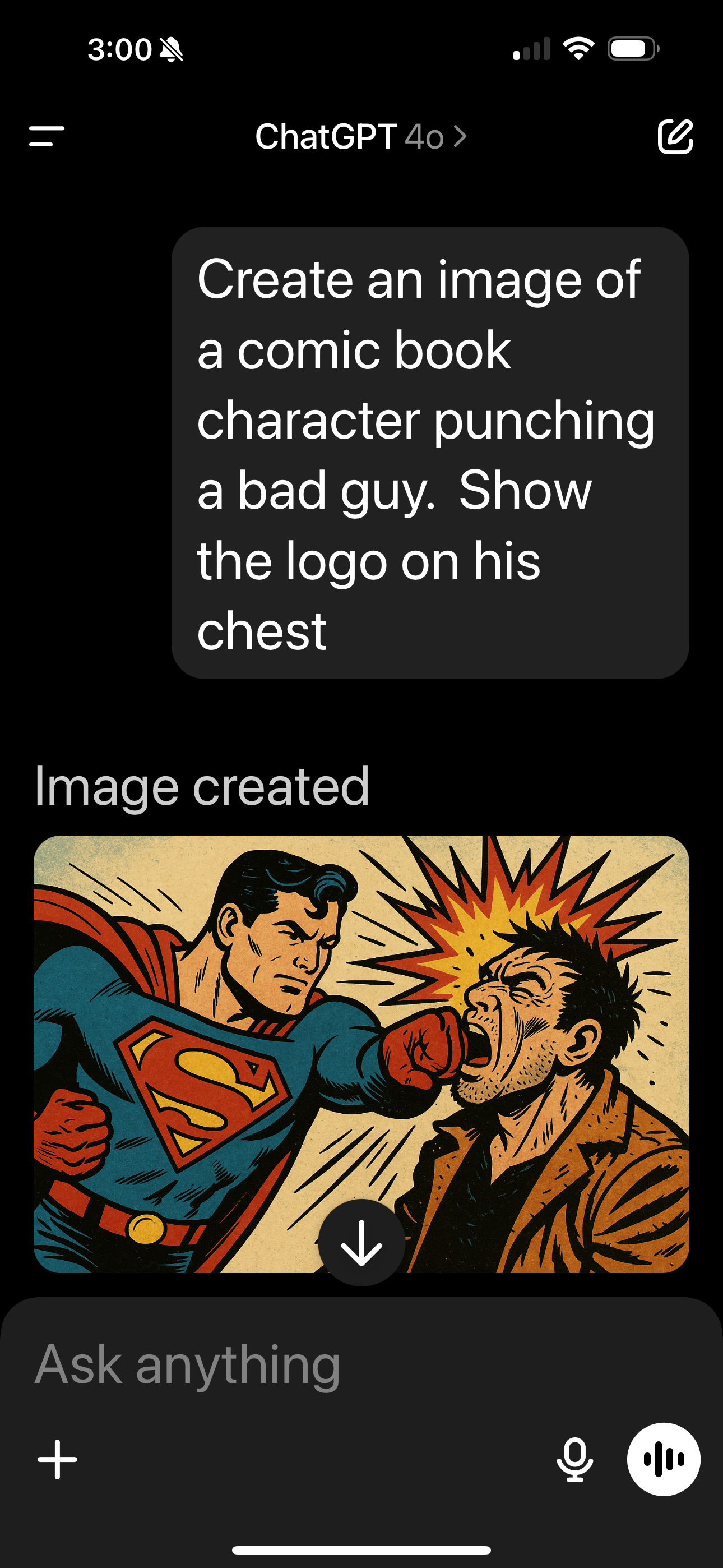

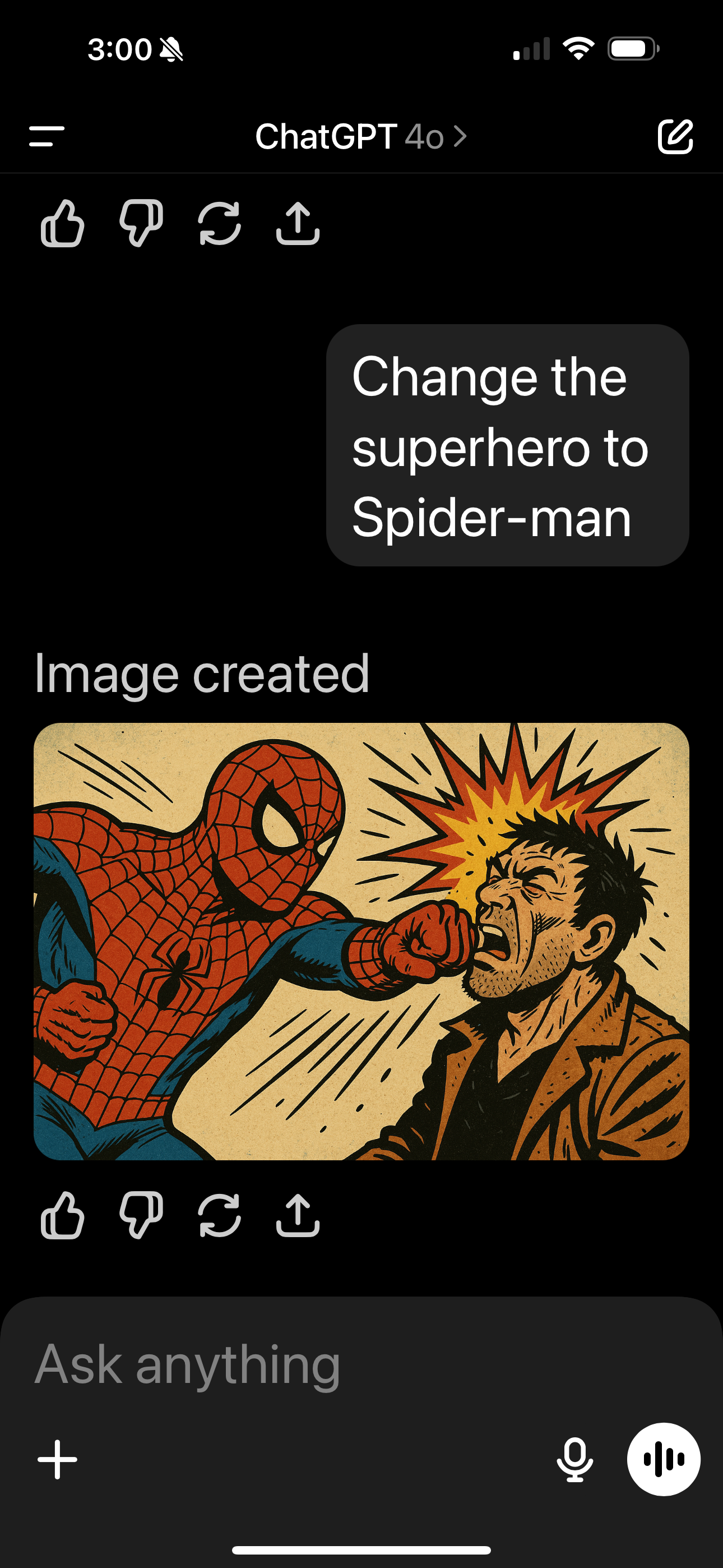

In both of these lawsuits, the plaintiffs were the authors of books, and both judges agreed that the the use of the books was transformative. And the filters implemented by Anthropic prevented Claude from repeating its training data verbatim. But not everyone is doing this. It's extremely easy to prompt ChatGPT to generate images that contain copyrighted material. Don't believe me?

When prompted, ChatGPT will produce images of Superman or Spider-man, whether or not you ask it directly.

I wonder what OpenAI used to train their image generation model? Did they license the complete collection of Superman comics specifically for the training of their model? What about Spider-man? Regarding the importance of the filters implemented in Claude, Judge Alsup states,

Users interacted only with the Claude service, which placed additional software between the user and the underlying LLM to ensure that no infringing output ever reached the users [...]. Here, if the outputs seen by users had been infringing, Authors would have a different case. And, if the outputs were ever to become infringing, Authors could bring such a case. But that is not this case.

For OpenAI, it doesn't seem like they're doing that. They aren't even trying. I think OpenAI would argue that it's the end-user's responsibility to not use the outputs of ChatGPT in any way that would infringe on anyone else's copyright, like how an individual can find copyrighted materials on Google Images, but it's their responsibility to not use those results for copyright infringement, not Google's.

However, I think the New York Times would disagree, as they (and several others) are suing OpenAI and Microsoft for copyright infringement. Their case has recently advanced, and they aren't just suing for direct copyright infringement, but also for the contributory copyright infringement by users of ChatGPT. Judge Sidney Stein states,

The Court finds that plaintiffs have plausibly alleged the existence of third-party end-user infringement and that defendants knew or had reason to know of that infringement. Accordingly, plaintiffs have plausibly alleged their contributory copyright infringement claims and defendants’ motions to dismiss those claims in all three actions are denied.

This will be an interesting case to follow, as the combined allegations of direct and contributory copyright infringement, as well as direct or indirect market substitution, make for a good argument against fair use. I'll be following this case, as well as the cases against Meta and Anthropic, which may be appealed.

The Gray Area

There are some scenarios where I think the training of LLMs (or other AI models) on copyrighted materials will ultimately be fair use. Take many of the OS-level Apple Intelligence features for instance, such as live translations, intelligent actions in Shortcuts, or writing tools. These features are transformative and don't substitute the market for their training data. In my mind, the line seems to be drawn around whether the LLM is being used for generative vs. non-generative purposes.

For generative AI, it's harder to argue for fair use if the model is capable of directly competing with the copyrighted material that was used to train it. For non-generative AI, the argument for fair use is more straightforward. The AI is being used to do something, not create something.

However, there is a gray area. When you're using an AI tool to summarize your notes or change the tone of an email, you could potentially argue that that's still "generative AI", in a sense, since the tool is technically generating text. But this use case still falls into my personal definition of fair use, since the tool is operating on the data you've provided it, and the contents of the training data aren't really relevant to the final output. The training data was used to build the LLM but isn't showing up in its outputs.

In the long-term, I wouldn't be surprised if generative vs. non-generative is where the line is drawn, and the arguments in court will shift from "Is it fair use?" to "Is it generative?".